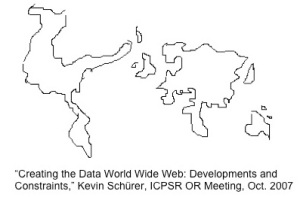

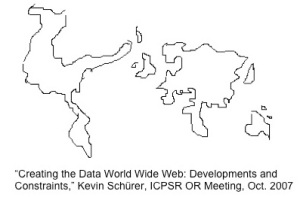

In October 2007, Kevin Schurer, who was then the Director of the U.K. Data Archive, made a presentation at the ICPSR Official Representatives Meeting at the University of Michigan about establishing a data world wide web.  He used this graphic to illustrate the current status of social science data curation around the globe. Each country has been crudely scaled according to the level of its social science data services. He noted that the U.S. and U.K. are disproportionally larger in this projection than their actual physical size because of the large volume of social science data curated in these two countries. He went on to say that Canada in his map is much smaller than its size because, “Canada can’t get its act together [regarding research data].” While this was a rather dismaying statement to have proclaimed about my home country in an international meeting, grounds exist for him coming to such a conclusion (see the introductory Blog item for evidence.) This observation about Canada raises two important questions:

He used this graphic to illustrate the current status of social science data curation around the globe. Each country has been crudely scaled according to the level of its social science data services. He noted that the U.S. and U.K. are disproportionally larger in this projection than their actual physical size because of the large volume of social science data curated in these two countries. He went on to say that Canada in his map is much smaller than its size because, “Canada can’t get its act together [regarding research data].” While this was a rather dismaying statement to have proclaimed about my home country in an international meeting, grounds exist for him coming to such a conclusion (see the introductory Blog item for evidence.) This observation about Canada raises two important questions:

- Who are Canada’s international peers in research data?

- How far behind is Canada in research data management infrastructure?

Canada’s International Data Peers

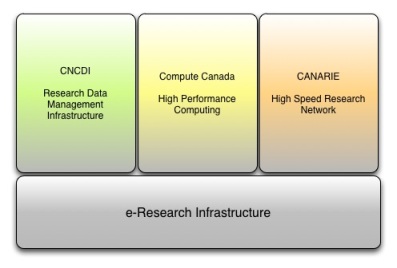

The Introduction to this Blog touched upon this topic. Canadians typically view their international research peers as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Germany. In many fields of research and in some areas of research infrastructure, this is the case. For example, CANARIE is a world-class research network that is comparable with Europe’s research network, GÉANT. Contributing to the validity of this comparison is the level of top-down impetus both receive through government policy, programs, and funding for these networks.

Research Data Management Infrastructure (RDMI) in Canada, however, does not compare with the developments in data infrastructure in these four countries. As mentioned previously, bottom-up actions by higher education institutions willing to collaborate with one another around cost-sharing initiatives are the driving force for RDMI in Canada, which by comparison is a very different environment.

Who then are Canada’s data peers? Looking at Shurer’s 2007 map, Canada appears to be grouped with the rest of the world outside the United States, Europe, and Australia. I had an opportunity to observe firsthand a few of Canada’s peers at a European Commission sponsored workshop on “Global Research Data Infrastructures: The Big Data Challenges,” held in Brussels in October 2011. The objective of this workshop was to further the development of a 2020 roadmap for global research data infrastructure. There were representatives from Africa, Asia, Australia, Canada, Europe, South America, and the United States, each asked to speak about data infrastructure in their country. I was asked to talk about data infrastructure in Canada.

The presenters from Brazil and Taiwan spoke about having to build data infrastructure from the bottom-up without the top-down guidance or incentives common in the U.S., Europe, or Australia. I was struck by how similar data infrastructure development in Brazil and Taiwan is to Canada. Who are Canada’s data peers? Nations building their RDMI from the bottom-up.

How Far Behind Is Canada From the Frontrunners on the Planet?

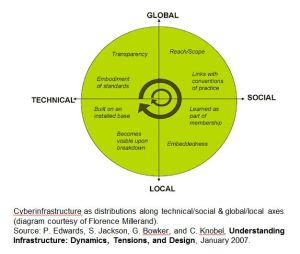

Internationally, RDMI consists of a real patchwork of activities regardless of whether the development is top-down or bottom-up. Looking at the various parts of the patchwork can provide different perspectives about where a country is positioned globally. This patchwork has been characterized as a Digital Science Ecosystem in the Global Research Data Infrastructure 2020 Roadmap (GRDI2020). Thinking of research data infrastructure as an ecosystem focuses attention on the complex relationships among important components of scientific research. To understand these complex relationships in an environment of data-intensive, multidisciplinary research is as challenging as it is to comprehend the interdependency among species in a biological ecosystem. The authors feel that the broader research environment is as much of a contributor to advances and transformations in scientific fields as technological progress (see p. 17).

The GRDI2020 report describes the Digital Science Ecosystem as being composed of Digital Data Libraries, Digital Data Archives, Digital Research Libraries, and Communities of Research. The relationships among these four components make up the patchwork environment in which this report envisions future scientific research to be conducted. From both a technical and organizational standpoint, relationships in a digital ecosystem are established and maintained through interoperability mechanisms among these four components. An earlier entry to this Blog highlighted the importance of institutions in preserving research data. Three of the GRDI2020 components are based on institutions: digital data libraries, digital data archives, and digital research libraries. The earlier Blog entry argued that these institutions do not have to be national, central services but can be distributed across existing institutions with a mandate to preserve research data. The success of such a distributed inter-institutional preservation network will depend on its interoperability across the network and with the wider research environment.

The GRDI2020 report describes the Digital Science Ecosystem as being composed of Digital Data Libraries, Digital Data Archives, Digital Research Libraries, and Communities of Research. The relationships among these four components make up the patchwork environment in which this report envisions future scientific research to be conducted. From both a technical and organizational standpoint, relationships in a digital ecosystem are established and maintained through interoperability mechanisms among these four components. An earlier entry to this Blog highlighted the importance of institutions in preserving research data. Three of the GRDI2020 components are based on institutions: digital data libraries, digital data archives, and digital research libraries. The earlier Blog entry argued that these institutions do not have to be national, central services but can be distributed across existing institutions with a mandate to preserve research data. The success of such a distributed inter-institutional preservation network will depend on its interoperability across the network and with the wider research environment.

This digital science ecosystem model can be used to assess the current state of research data infrastructure in a country. Putting aside the various challenges of top-down or bottom-up development, what aspects of the four components of the GRDI2020 ecosystem does a country have? Furthermore, what interoperability relationships have been established among these components? Looking specifically at Canada, a strong network of data libraries exist on campuses across the country because of the Data Liberation Initiative (DLI). Since 1996, academic libraries have provided data services to support the dissemination of standard data products from Statistics Canada. In addition to providing access to data, DLI also conducts annual training regionally in Canada, constantly upgrading the skills of those who provide data services on their local campus. Compared to Europe, Canada is much farther along in developing a network of data libraries that support local access to data. Canada also has a strong network of research libraries with large and growing digital collections, including repository services for research results. The Achilles heel for Canada is digital data archives. This is the ecosystem component for which Canada lags far behind the U.S., U.K., Australia, and Germany, although a few research libraries are beginning developments in this area that hopefully will begin to close the gap. The Canadian Polar Data Network is an example of a new Canadian collaborative, inter-institutional, cross-sectoral, distributed data archive that serves as a model for other Canadian institutions to emulate.

With strategic top-down investment in data preservation services, Canada could have leapfrogged to be among the frontrunners in the digital science ecosystem. In the absence of top-down development, research libraries working collaboratively with research communities must build from the bottom-up to establish data preservation services. The engagement of senior administrators at Canadian universities in the development of research data infrastructure is critical to a bottom-up strategy. There is a need for university policies that establish an institutional mandate to preserve research records and that identify institutional data stewardship responsibilities covering the research lifecycle.

Finally, taking on these tasks at the institutional level will help begin the conversation between universities and national funding agencies around the bigger question of who should be doing what regarding data. Currently, both parties are at loggerheads on this topic.

[The views expressed in this Blog are my own and do not necessarily represent those of my institution.]